By Julius Melnitzer | March 29, 2022

Pressure to pursue climate-change strategies that address Scope 3 emissions — those generated not through operations but across the value chain — is mounting on Canadian companies, despite challenges posed by a lack of regulatory guidance and the breadth of the category itself.

“Investors’ focus is gradually shifting from examining responsibility for reducing operational emissions to determining which companies are transforming their business models to give us the best chance of achieving climate-change goals, both towards and beyond net-zero 2050,” said Eyab Al-Aini, a senior analyst in the Pembina Institute’s responsible fossil fuels program. “The key question is becoming ‘What are companies enabling or not enabling through their overall activities?’”

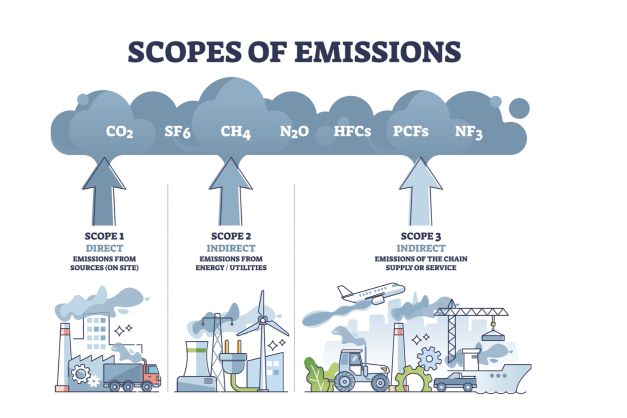

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol, a globally-recognized standard for measuring and managing GHG emissions from companies and their value chains, recognizes 15 categories of Scope 3 emissions. The most significant are “purchased goods and services” and “use of sold products.”

As it turns out, Scope 3 is often where the greatest impact occurs.

In the oil and gas sector, for example, Scope 3 emissions are primarily downstream emissions that occur when petroleum products are combusted. Not surprisingly, according to MSCI, an international investment consultancy, these emissions “dominate the overall carbon footprint” of the integrated oil and gas industry, representing “more than six times the level” of its combined Scope 1 emissions (emanating directly from operations, like running machinery or vehicles) and Scope 2 emissions (indirect emissions produced on a company’s behalf, like energy purchased for heating and cooling).

“Emissions-wise, Scope 3 is nearly always the big one,” said a recent report from Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. “For many businesses, Scope 3 emissions account for more than 70 per cent of their carbon footprint. For example, for an organization that manufactures products, there will often be significant carbon emissions from the extraction, manufacture and processing of the raw materials.”

The upshot is that companies that have low operational emissions but high Scope 3 emissions, such as technology companies, may face financial difficulties relating to policy risks, carbon pricing and shifts in end-product market demand if they don’t address supply line changes.

“We’re seeing more of a ‘whole economy’ approach to climate change where investors are differentiating between companies in making their long-term portfolio decisions,” said Al-Aini. “And if what investors foresee is a very low emissions economy, it’s in companies’ best interests to align with that vision so they remain competitive in the long term.”

But here’s the rub: Scope 1 and 2 emissions are far more likely to be within an organization’s control than their Scope 3 counterparts. This lack of control makes calculating Scope 3 impacts by factoring in supply chains and products’ use a complex, if not convoluted process. The lack of control also present challenges in managing these emissions.

Compounding the issue is a lack of regulatory guidance.

“A well-crafted, robust policy that spans different levels of government and takes into account the diverse perspectives of the various sectors affected would go a long way to relieving the uncertainty that exists about Scope 3 disclosure and management,” Al-Aini says. “But there are always going to be fine lines, both because some sectors are more suited to disclosure than others, and because a sweeping policy would make life difficult for small companies that lack adequate sustainability teams.”

So although a company’s supply chain emissions are on average 5.5 times larger than its Scope 1 and 2 emissions, according to CDP Global, the not-for-profit charity that runs the global disclosure system for environmental impacts, action in this arena, according to Business for Social Responsibility (BSR), a global sustainable business consultancy, “remains fragmented and limited.”

As Benjamin Israel, now a senior coordinator, energy at the Government of Northwest Territories, noted in a 2020 blog he wrote as a senior analyst for Pembina, “not a single Canadian oil major has committed to addressing” all of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.

On the other hand, Enbridge Inc., the first midstream company to commit to net-zero, has a long history of addressing Scope 3.

“Despite the current limited guidance defining Scope 3 emission parameters for our sector, we have been tracking and reporting on these emissions since 2009,” said Pete Sheffield, the company’s chief sustainability officer, in an email responding to questions from Financial Post.

Enbridge currently reports utility customer natural gas usage, employee air travel and electricity grid loss. In 2021, the company added new Scope 3 metrics tracking the emissions intensity of the energy it delivers and the emissions avoided through its investments in renewables, low carbon fuels and conservation programs.

Otherwise, Enbridge is working to clarify the parameters of Scope 3 emissions practices for the midstream sector by collaborating with the Science Based Targets initiative, which helps companies set science-based emissions reduction targets, as well as with other groups.

Will others follow suit? That depends, Al-Aini said, on how quickly and aggressively investors get on the Scope 3 bandwagon.

“Governments are the last to act,” Al-Aini said. “The first people are the scientists, then the public gets the message, then investors — the people to whom corporations are really attuned — start paying attention, at which point they look at companies and ask for the data.”

RELATED STORIES

Ottawa’s last-minute intervention in energy projects eroding Canadian regulators’ independence

Manitoba v. Ottawa: Why the province lost its legal challenge against the federal carbon tax

Rising municipality charges stalling efforts to develop green buildings in Canada

Should companies fear the Clean Fuel Standard?

Bill C-12: Why the Green Party and environmental groups are against Ottawa’s net-zero climate bill

Julius Melnitzer is a Toronto-based legal affairs writer, ghostwriter, writing coach and media trainer. Readers can reach him at [email protected] or https://legalwriter.net/contact.