Given the number of natural resource projects that have Indigenous support, this type of litigation could become more frequent

A pair of disputes in Newfoundland and Labrador and Alberta relating to resource projects on Indigenous territory, suggests that federal and provincial governments still don’t get it when it comes to their well-established duty to consult with First Nations.

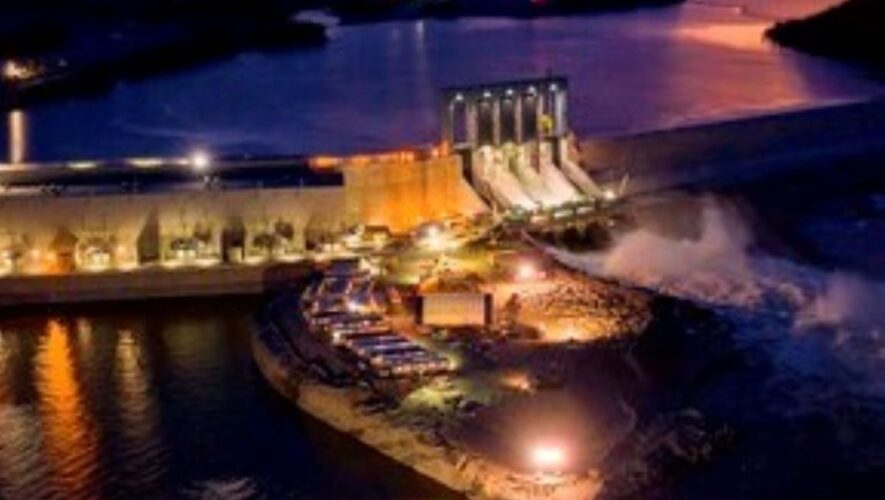

In Newfoundland, the Innu Nation is suing the feds and the provincial government for failing to consult before negotiating the 824-megawatt Muskrat Falls hydro dam bailout agreement, a $5.2 billion aid package aimed at helping the province deal with the massive debt arising from billions in cost overruns at the project. The agreement amounts to a rate mitigation deal that protects Newfoundlanders from electricity rate shock resulting from the overruns.

The Innu, however, maintain the deal could significantly affect the impact benefits agreement (IBA) signed with Ottawa and the province in 2011. Under its terms, the Innu enabled the Muskrat Falls project by allowing Newfoundland to flood Innu territory roughly the size of Delaware.

“As compensation for the harm that the project would entail, the Innuit Nation received five per cent of the net cash flow from the project,” says Matt McPherson, a Toronto-based partner at Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP, which represents the Innu. “But the rate mitigation arrangement will certainly have an impact and perhaps a significant impact on the profits that flow to the Innu.”

According to McPherson, the Innu were excluded from the rate mitigation negotiation process and have not been provided with adequate information about its impact.

“We have repeatedly requested information since 2020, but all we received were assurances from the provincial government that they would honour the commitments in the IBA,” he said.

The Innu didn’t find out about the successful conclusion of an agreement in principle on the bailout until 5 p.m. on July 27, the day preceding the formal announcement.

“No details were provided, and the only way the Innu got even basic information was by crashing the party at a technical briefing the next day — to which they hadn’t been invited,” McPherson said.

Eventually, the authorities did release further details, but not the financial modelling that was necessary to determine the deal’s impact.

“We know the information was available because the government has stated publicly that the modelling was part of the negotiations,” McPherson said.

Frustrated, the Innu filed a claim against the governments on August 10. The claim alleges breach of the duty to consult, breach of the honour of the Crown, and breach of fiduciary duty. The Innu also see an injunction prohibiting conclusion of a final agreement before the issues raised in the lawsuit are resolved.

Previous jurisprudence suggests the Innu have a strong claim.

In mid-July, Federal Court Justice Henry Brown recognized the Crown’s duty to consult on economic benefits linked to Aboriginal rights. Consequently, Brown quashed federal environment minister Jonathan Wilkinson’s decision allowing Coalspur Mines Ltd. to submit the proposed expansion of its Vista thermal coal mine near Hinton, Alberta to the federal impact assessment agency.

As it runs out, the Ermineskin, like the Newfoundland Innu, had entered IBAs related to the existing mine. But Wilkinson didn’t bother contacting the Ermineskin, let alone consult them. This was wrong, the Ermineskin argued, because the designation to the agency affected their economic interest in the expansion.

Brown agreed, noting that the IBAs were entered into after consultation and provided “valuable economic, community and social benefits to Ermineskin,” and were “intended to compensate Ermineskin for potential impacts caused by natural resource development on the ability of Ermineskin members to exercise Aboriginal rights within their Traditional Territory.” It followed that they had been “inexplicably frozen out” from a “one-sided process”.

“The court’s conclusion that interference with an IBA can trigger a duty to consult on economic benefits linked to Aboriginal rights is path-breaking,” said Dr. Dwight Newman, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Rights in Constitutional and International Law at the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Law.

And if upheld, the precedential effect of the Coalspur case on the Innu rate mitigation dispute, could be significant given that IBAs are central to both cases. As well, it’s clear that Canadian judges prefer consultation to litigation and have carved out a broad swath for the duty to consult.

“Judges, including the Supreme Court of Canada, have repeatedly said that we don’t want to deal with these, so please negotiate,” McPherson explains.

According to Thomas Isaac, the Vancouver-based chair of Cassels Brock LLP’s aboriginal law group, the disputes emanating from IBAs are a “natural progression” of the positions of both the Indigenous people and governments.

“What you’re seeing is a very sophisticated First Nations who are thinking in generational terms and making government-like decisions about taking care of people and building infrastructure,” he said. “On the other hand, you have federal and provincial governments who have not developed a vision about the balance between governing the interests of all Canadians and acting honourably in furtherance of their constitutional obligations to Aboriginal people.”

In practical terms, Isaac adds, government need to treat IBAs with an eye to their implementation going forward.

“Governments must understand that they must mean and give effect to every word in every single agreement in IBAs,” he said.

Julie Abouchar, a Toronto-based partner at Willms & Shier, an environmental, Aboriginal and energy law boutique, agrees that the duty to consult about the impact of projects is an ongoing one.

“Projects impact the ability to exercise Indigenous rights and that doesn’t change during the life of the project,” she said. “That’s why the need to consult continues.”

And that applies both to projects that do and don’t have Indigenous support.

“We may see Indigenous people resort to litigation against governments that turn down projects which they would like to see proceed,” says Roy Millen, an Aboriginal law partner in Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP’s Vancouver office. “Given the number of natural resource projects in Canada that have Indigenous support, this type of litigation could become more frequent.”

Julius Melnitzer is a Toronto-based legal affairs writer, ghostwriter, writing coach and media trainer. Readers can reach him at [email protected] or https://legalwriter.net/contact.

RELATED ARTICLES

Bare Bones Briefs: Duty to consult is double-edged sword

Is Trudeau’s support for UNDRIP a meaningless ploy?

Government should be honest about its support for UN Indigenous rights resolution

Why B.C.’s Indigenous rights bill is ‘impractically broad’ and inconsistent with Canadian law

You and all your quoted experts left Hamlet out of the play in this item.

Bill C 15 had received Royal Assent and so was law before the bailout!

So the requirement was no longer for mere consultation, but consultation leading to FP and I consent to any government action which “may affect them”. See UNDRIP generally and particularly Article 19.

Here then is a case for the Supremes to be forced to attempt to translate that crock of UN dreams into real law. And Justin can be proud that he put Canada beside Bolivia (and it’s indigenous former president Marxist Evo Morales) as the only two nations on earth foolish enough to turn UNDRIP into the law of the land.

Best regards, Michael

PS Feel free to print this comment.

—

J. Michael Robinson QC